Local governments have made a quantum leap in dealing with mental, behavioral health crises

Cities, counties -- often in partnerships -- are deploying new programs to help their citizens who are experiencing psychological emergencies

The way cities and counties deal with a citizen in a mental or behavioral health crisis has changed in the same way Hemingway wrote about how bankruptcy occurs: gradually, and then suddenly.

It was just a decade or so ago when I heard about a police chief who would replay calls of someone in the middle of a break from reality to fellow department directors during their weekly meetings.

Many folks at the meeting found them amusing. Others sat stone-faced, recognizing that severe mental health disorders are no laughing matter. I know from personal experience no one would wish serious mental health problems on their worst enemy if they’ve had to live with it for any significant period.

I can’t imagine a law enforcement officer doing that today.

Back then, there wasn’t much cops could or would do to help someone in that condition unless they were at risk of harming themselves or others. Thankfully that has changed — and quite suddenly, it seems to me.

I reached out recently to some gov comms peers asking if their jurisdictions have adopted the new approach of having mental health professionals assist with these kinds of 9-1-1 calls. Within hours, I heard from nearly two dozen folks in counties and cities large, small, and in between.

Hallelujah.

What I learned as I looked at the various programs was that responsive, thoughtful government is alive and well in this country. That said, getting to this inflection point came with unimaginable pain, trauma and, in too many cases, death.

An example is the story of Miles Hall, a 23-year-old Black man who was tragically killed by law enforcement while suffering a severe mental health incident. Before the incident, Miles’ mother, Taun, found there were no places for him to go to get help unless he was a danger to himself or others, or gravely ill.

After Miles’ death in 2019, his mom advocated for system-wide change to prevent unnecessary suffering and loss of life. Her efforts help create the A3 Crisis Response program in Contra Costa County, California (pop. 1 million). Here’s a video explaining the program, which includes Taun sharing some of Miles’ story.

I’m not ashamed to say I get choked up watching that video. These are dedicated public servants who are helping their constituents when they have nowhere else to turn. I love the story shared by Kristin, the community support worker:

“I had one mother tell me over the phone, I’ll never forget it, at the end of our conversation she said, ‘I was alone in the middle of the ocean on this little life raft. After speaking to you, I feel like this big rescue ship is coming toward me.’”

Hallelujah and amen.

As often is the case, not everyone is delivering these services in quite the same way, though there are similarities. By sharing how governments are doing this across the country, my hope is those jurisdictions who haven’t deployed these kinds of programs will do so, and those who have them will learn how to make theirs even better.

I don’t think I need to make the case that every local government — even those with smaller populations — should do more to respond to those in a mental or behavioral health crisis. But don’t take my word for it.

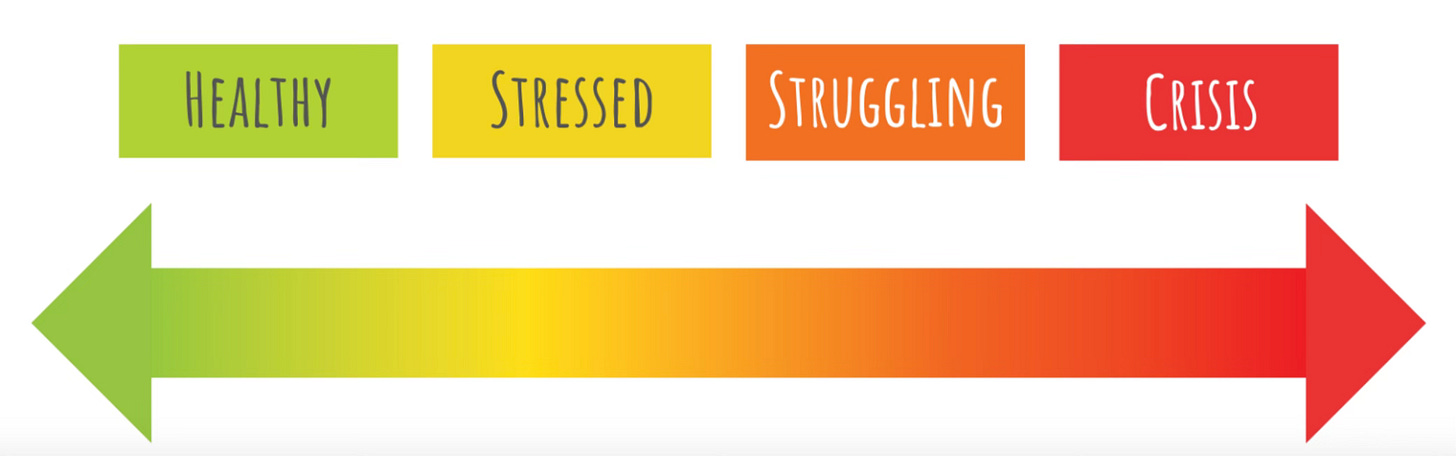

Bryce Boddie, senior director of behavioral health services at Hill Country Family Services, is on the steering committee of the Kendall County Behavioral Health Advisory Coalition, an initiative to coordinate and improve mental health response and care in a rural county of 45,000 just north of San Antonio. Bryce likes to share this behavioral health spectrum chart to help explain the need for improving how we serve those in mental health crisis.

“I don’t care who you are, at some point you or a family member or someone you love has been in the red zone,” he says. “If you say you haven’t, you’re lying.”

Bryce says most folks can get out of that red area quickly “because we have support, family, things we can access. But there are a whole lot of folks who can’t do that.” The coalition in Kendall County was formed last year to help those folks. Joining Bryce on the steering committee is the county sheriff, the police chief and city manager of Boerne — the largest city in the county — the superintendents of both school districts in the county, the district attorney, and leaders from the two largest mental health service providers. If it takes a village to raise a child, it also takes a village to help that child when he grows up and his life goes off the rails due to mental health problems.

I should note the City of Boerne (pop. 21,000) won a prestigious ICMA award for its role in the collaborative program. From Boerne’s news release about the award (shoutout to comms director Chris Shadrock):

The Boerne Police Department created its first-ever mental health officer position in January 2022, filled by Officer Rebecca Foley, to address increasing calls for mental health response. Officer Foley responds to mental health calls, accompanies patients to hospitals on emergencies, and connects them to mental health resources in the days and weeks that follow.

Officer Foley also works closely with school resource officers, school counselors, and administrators to address at-risk youth with mental health needs within the district. Having a dedicated MHO ensures patients receive dedicated care and allows patrol officers to return to other duties more quickly.

“This can be replicated by any city of our capacity,” Foley said. “At first, everyone was hesitant to talk about this, but now I have mothers we are helping who say, ‘Thank you, I appreciate this.’”

Kendall County’s neighbor to the south, Bexar County (pop. 1.7 million), started its SMART program in October 2020 at a cost of $1.5 million. SMART is an acronym for Specialized Multidisciplinary Alternate Response Team. It serves the unincorporated area of the county along with 26 suburban cities. Like many of these programs, it pulls together resources from various agencies to deal with the complexities of responding to and following up with their constituents in need. Here’s a great video that explains the program (shoutout to Bexar County PIO Monica Ramos).

As Mike Lozito of the Office of Criminal Justice says in the video, “You want to take the time with those individuals, and sometimes our response time is 45 minutes, talking to that person and making sure they’re OK so the officer doesn’t have to go back there again. That’s really the goal, is to be more proactive than reactive.”

The follow-up is fundamental to a successful program. Boddie, of Kendall County, says navigating the mental health system is a big part of what he does to help folks once the crisis has passed. If you don’t have insurance, it’s usually hurry up and wait to get an appointment with a therapist or a bed in a stabilization facility.

That wait is one reason why Bloomington (Minn.) Police Chief Booker Hodges launched a program in October to provide in-home therapy services. Bloomington is a Minneapolis-St. Paul suburb of 95,000. From the city’s news release announcing the program (shoutout to City PIO Erik Juhl):

Last year, BPD responded to 1,115 calls related to a mental health crisis or suicide attempt/threat. So far this year, there have been 952 calls. In many cases, follow-up therapy sessions are not available for weeks after the initial contact with law enforcement and social workers. Without professional treatment and intervention, the potential for repeat incidents increases.

“Our core value here at the Bloomington Police Department is respect, and respect is demonstrated through our compassionate and honest service. I believe that it’s not very compassionate to allow someone who needs and wants help to go months without getting the help they need,” Chief Hodges said. “Our social workers encounter people who need immediate therapy. Unfortunately, that therapy is rarely available, and even when it is, the price is too much for many families. Our Rapid Response Mental Health pilot program looks to ensure those who need help are being served as soon as possible with compassion and respect.”

The Bloomington program is funded, in part, from opioid settlement funds. And, for the record, I would run through a brick wall for Chief Hodges.

My review of these programs found most are housed in law enforcement. But the Crisis Response Unit (CRU) in Round Rock, Texas, (pop. 130,000) lives in the Fire Department, and was a natural outgrowth of the department’s Community Risk Reduction program we profiled in December. The video below explains how CRU, created in 2022, works with hand-in-glove with Round Rock police to deliver the kind of care that more and more local governments are being asked to deliver.

“Just to have the depth of service here in Round Rock is super exciting,” says Annie Burwell, CRU program manager. “Because we go in and say, ‘What can we do to make things better, easier, safer for everyone’, and we have all these tools and that is really cool.”

Round Rock’s CRU responded to 1,782 calls in 2023.

One program, in Overland Park, Kansas (pop. 212,000), includes a therapy dog, Haven. Here’s another great video (shoutout to city comms manager Meg Ralph) which explains how officers are trained to de-escalate situations, which includes wearing uniforms and driving vehicles that are different from standard law enforcement. The Overland Park Crisis Action Team includes specially-trained crisis intervention team specialists and mental health co-responders from Johnson County Mental Health.

“The fact we can actually bring a clinician in, that’s what makes this work and that’s what makes this special,” Sgt. Stewart Brought says in the video. “We can bring them in and remove the (law enforcement) officer element as much as possible, hence the uniforms, the cars, everything about this is different. We’re still police officers, but just the fact we look different … the way we approach people, whatever it is that’s different, is making an impact. And there’s people that have absolutely said that on calls, ‘I’m not talking to them (officers in regular uniforms) but I’m talking to you.’”

In Tallahassee, Florida (pop. 196,000), four city departments (police, fire, dispatch, and housing & community resilience) partner with a regional mental health provider to respond to non-violent 9-1-1 calls for service with individuals experiencing a mental health crisis. Within one hour of its activation in April 2021, the TEAM (Tallahassee Emergency Assessment Mobile Unit) got its first call. I’m surprised it took that long. Each year, the city takes approximately 2,300 non-violent calls for mental-health related help. (Shoutout to comms chief Alison Faris with the City of Tallahassee.)

In Douglas County, Colorado (pop. 369,000), the Community Response Team (CRT), established in 2017 by the Douglas County Mental Health Initiative, pairs a law enforcement officer with a mental health professional to help adults and youth experiencing a mental health crisis avoid the emergency room or jail and get the help they need. Per the Douglas County website: In 2019 two additional teams were added allowing coverage of the entire county. As of 2023, there are nine teams — including officers and deputies from Castle Rock Police, the Douglas County Sheriff’s Office, Lone Tree Police, and Parker Police — with response capability seven days a week. (Shoutout to Carrie Groce with the City of Castle Rock.)

The City of DeSoto, Texas (pop. 55,000) utilizes a similar model, says PIO Matt Smith.

“The City of DeSoto worked with Dallas County, neighboring cities, and community leaders/activists following the killing of George Floyd in May 2020 to come up with more effective and less harsh ways of responding to issues related to mental health and residents in crisis,” Smith says.

They created a Regional Care Team with neighboring cities Cedar Hill and Duncanville to follow up with those experiencing a crisis and their families, generally after an initial police response. The DeSoto CARE Team is affiliated with DeSoto Police but includes team members from other City departments and employees with backgrounds in social work and mental health training. At first, the team was housed in the city library but now operates from a shuttered school to keep their settings neutral or less intimidating, Smith said. Support from the Dallas County Commissioners Court led to a $1.8 million grant so the CARE Team can expand regionally.

The City of South Portland, Maine (pop. 27,000) has had two behavioral health liaisons in its police department for six years, says PIO Shara Dee. This seems to be one of the more seasoned programs. Here’s some qualitative and quantitative information to share on its effectiveness:

One of the behavioral health liaisons is credited with saving the life of a suicidal person last March.

A study of arrest data concludes the City “should continue to invest in community-based services and interventions that help people who are unhoused, in crisis, and/or grappling with mental health issues,” researcher Sarah Groan said.

And that’s exactly what the city has done.

The City of Olympia, Washington (pop. 56,000) has a Crisis Response Unit (CRU) that provides mobile response to community members experiencing problems related to mental health, poverty, houselessness, and substance use. It’s been in operation since 2019, when it made 3,166 citizen contacts. The CRU includes a Familiar Faces program that “uses peer specialists for people identified as our most vulnerable population in the downtown area experiencing complex health and behavior problems,” according to the city. “Recognized as the highest utilizers of emergency services with frequent and persistent contact with Olympia Police officers, Familiar Faces peers offer an empathetic approach because their shared life experiences, non-judgmental, and unconditional support is invaluable to those historically resistant to support and resources.”

Just down the road in Covington, Washington (pop. 21,000), the city recently created a new position for a community care specialist. “He is on city staff, is former law enforcement but has gone into the Human Services side of things,” city PIO Karla Slate says. “Our officers call him in when they respond to a call that is better suited for him to assist with something involving homelessness, mental health issues (that aren’t of criminal level), drug addiction issues, etc. His main goal is to connect those individuals with services that can help them like shelters, clinics, rehab, etc. … (W)e are a smaller city, so it works for us for now to address some of those issues that aren’t always best served by police.”

If these examples aren’t enough to get your local government to improve the way it deals with these kinds of issues, visit the National Alliance on Mental Illness website’s By The Numbers page. It’s sobering (and they’ve created a bunch of helpful infographics to tell the story). Here’s the TL;DR:

1 in 5 U.S. adults experience mental illness each year

1 in 20 U.S. adults experience serious mental illness each year

1 in 6 U.S. youth aged 6-17 experience a mental health disorder each year

50% of all lifetime mental illness begins by age 14, and 75% by age 24

Suicide is the 2nd leading cause of death among people aged 10-14

It is intensely gratifying to see so much great work being done in this area. In future newsletters we’ll do a deeper dive into some of these programs and the impact they’re having.

Onward and Upward.

Healthy, stressed, struggling, crisis.

This is the spectrum.

The categories are real but fluid,

always moving in one direction

or the other.

Some, the fortunate among us, have experienced the healthy state.

ALL of us have experienced the three miserable unhealthy states.

Do not send to know

for whom these beautiful devoted servants arrive.

They arrive for thee.

How ironic that at the same time

as political democracy in our country is in crisis,

mental health democracy in our towns and cities

is on the rise!

These loving local workers are building

the foundations of our nation's mental health.

They are reaching out and reconnecting our isolated souls

one person at a time.

"I was alone in the middle of the ocean on this little life raft.

After speaking to you, I feel like this big rescue ship is coming toward me.’”

The visionary individuals creating these responsive local programs

are leading the way toward a new birth of freedom

for those of us suffering psychological pain and distress.