The COVID Vaccine Rollout: Lessons on Communication and Trust

A public health expert's thorough, no-nonsense review of the COVID vaccine rollout holds lessons for all public officials

Hey there! As we jump into today’s issue on the hard-earned lessons from the COVID vaccine rollout, please note that you’ll encounter a paywall midway through. To keep you from missing out, I’m offering a special discount on annual paid subscriptions, valid for one week only.

Subscribe today using this link and unlock this full issue, plus all the exclusive perks of being a paid subscriber — like the ability to book office hours with me — for the next 12 months. Don’t wait too long; this offer expires in a week. Let’s keep learning together!

As promised in this week’s TL;dr on hurricane misinformation, today we’re reflecting on the COVID vaccine rollout through the lens of a public health official. Her perspective is, in a word, magnificent. It’s the kind of honest, hard-nosed, let’s-not-screw-this-up-again kind of after-action report every public agency should conduct after a crisis. Dr. Kristen Panthagani’s work is so well-crafted, I’ll be sharing numerous direct quotes and graphics from her series to ensure her insights come through in their original form.

The four-part series from Your Local Epidemiologist offers an unfiltered review with practical recommendations for government officials. The lessons learned can be applied to any controversial issue that public officials may face. This is GGF goodness of the highest order.

Here’s a quick overview of why her analysis is so effective:1

What’s the Problem? Panthagani is tackling the erosion of public trust in vaccines, a problem exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic by communication missteps, unrealistic expectations, and shame-based messaging. She argues these issues have fueled vaccine hesitancy, not only for COVID-19 vaccines but also for other vaccines and public health initiatives more broadly.

Why Is She the Right Person to Be Addressing This Problem? Panthagani is a resident physician and Yale Emergency Scholar who is completing a combined Emergency Medicine residency and research fellowship focusing on health literacy and communication.

How Is Her Approach to Dealing with This Problem Reasonable and Responsible? Panthagani’s approach is grounded in science and compassion. She advocates for transparency, acknowledging uncertainties, and setting realistic expectations — strategies that are critical for responsible public health communication.

Is She Listening and Does She Care? Panthagani demonstrates empathy by validating the public’s confusion and frustrations around COVID-19 vaccines. She avoids dismissive language, carefully considers public perceptions, and advocates for values-based communication that resonates with people’s identities and beliefs.

Panthagani takes a thoughtful, empathetic approach that acknowledges past mistakes while offering a path forward that prioritizes respect, transparency, and the well-being of the community. So, let’s get to the heart of the matter.

Misinformation vs Miscommunication

In the first installment, Panthagani begins with this statement:

The Covid-19 vaccines are undoubtedly among the most impressive medical feats in history. One model estimated that Covid-19 vaccines prevented 20 million deaths worldwide in their first year alone. As a physician-scientist, watching the scientific world come together to produce not one but multiple vaccines in a matter of months in the midst of a global pandemic has been truly awe-inspiring.

But that is not how many people remember them.

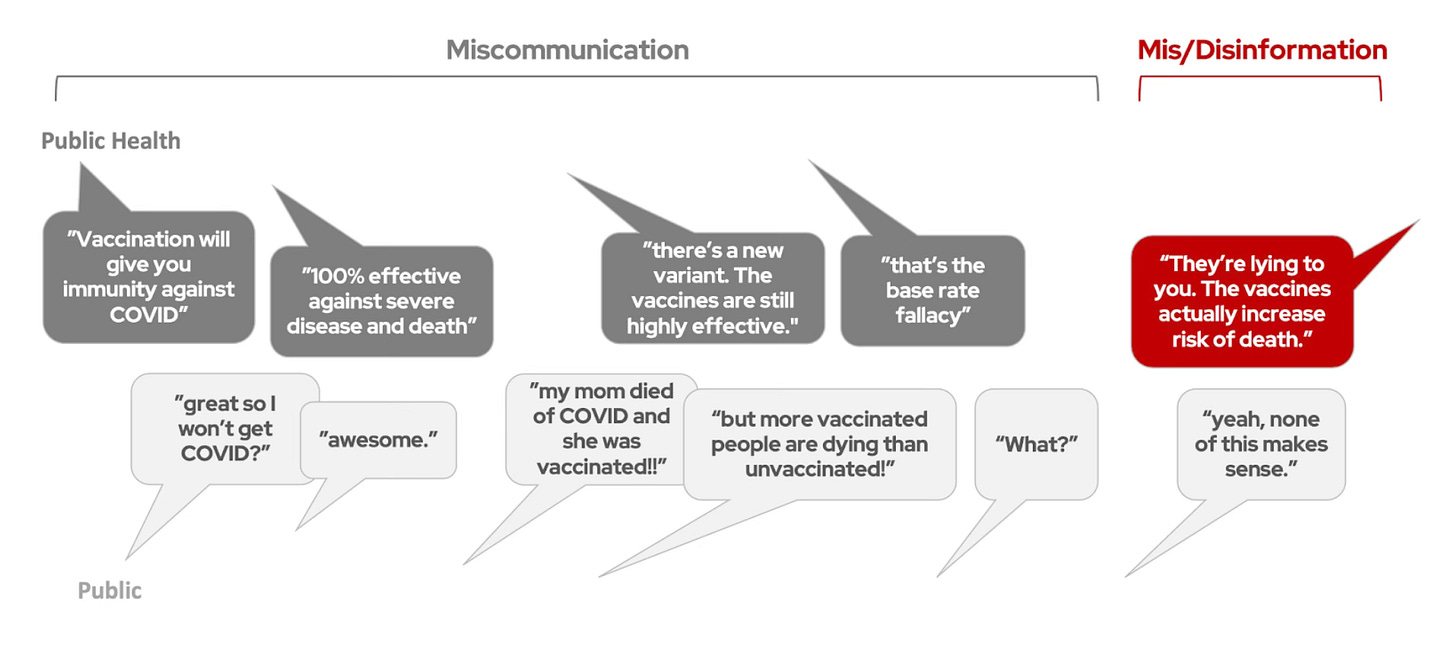

The core issue, she writes, is that what was communicated about the new vaccines wasn’t what the public perceived. Her graphic sums it up well.

“When valid questions aren’t answered adequately or from a place of empathy, it’s not unreasonable that trust declines,” she writes.

Panthagani notes “it was h.a.r.d. to communicate to a polarized nation during a deadly pandemic when yesterday’s data was already outdated.” I can only imagine. She’s also rightly focused on where public health officials should be focused in the future as regards misinformation.

Misinformation is not going away, and we can (and will) keep addressing rumors as they come. But the generation of these rumors is, for most of us, completely out of our control. In the public health and medicine field, we should be far more interested in looking at what is within our control: our communication, and how we can do better.

Setting Realistic Expectations

In the second post in the series, headlined, “Why did Americans expect a perfect COVID vaccine?” she gets right into what needs to be done better: expectation management and clarity over what constitutes immunity.

In June 2020, she notes “the FDA guidance on what must be achieved by the vaccines to gain approval was 50% efficacy.”

And that’s not just efficacy against infection—even a 50% reduction of severe disease or death would have met the FDA’s threshold. Dr. Fauci said a vaccine with 70% or 75% efficacy would be “terrific.”

Were the public’s expectations set? No. There was so much other pandemic news—hospitals were overloaded, new rumors were popping up daily, and we were going 2,000 mph trying to keep up with communicating to the public. We didn’t know if we would get a vaccine in six months or three years, never mind the details about how well it would work. Setting the public’s expectations about vaccine efficacy and anticipating concerns was, understandably (but mistakenly), much lower on the priority list than the biotechnology itself.

When the results of the Pfizer and Moderna trials were released later that year they showed an astonishing 90% efficacy.

“It cannot be overstated just how good this news was,” she writes. “Over 300,000 people had died from COVID-19 in the U.S., and finally, some hope was on the horizon.”

But the good news got overstated and then miscommunicated.

The >90% efficacy above referred to efficacy against symptomatic infection. A second outcome was also reported: 100% efficacy against severe disease and death. In reality, the clinical trials were not big enough to accurately measure this—they were statistically powered around symptomatic COVID-19 infection, not hospitalization or death. This “100%” number was a ballpark, not a precise estimate.

But soon, it became a widely circulated talking point. To encourage people to take the first vaccine available to them and not wait for their favorite vaccine, people were reminded: all three COVID vaccines were 100% efficacious in preventing severe disease and death.

Compounding this error is the general public’s lack of understanding about how immunity works, Panthagani writes.

“In science, immunity describes one of humankind’s most complicated biological systems. There are multiple types of immunity, and the degree of immunity someone has can vary dramatically depending on a wide variety of factors. But in everyday language, ‘immunity’ often implies something much simpler: complete protection from something.”

When the public hears 100% efficacious, we assume that means we’re never going to get COVID, i.e, the vaccines are perfect. And that’s wrong. Here’s why:

Experiences with childhood vaccinations reinforce this simpler interpretation of immunity as perfect protection. Rates of diseases like mumps, measles, and polio are extremely low for vaccinated people in the U.S. for two reasons: the vaccines have high (but not perfect) efficacy, and people are unlikely to encounter those diseases in the first place due to herd immunity from vaccination.

For many, this leaves the impression that immunity from vaccination = you’re not gonna catch the disease, ever. The hidden effect of herd immunity makes those childhood vaccines seem essentially perfect.

When breakthrough infections started to happen — that is, when folks who got the jab wound up with COVID — many believed they had been lied to. Many also began to say (and I’ve heard this myself from friends who are now vax skeptics) that the COVID vaccines weren’t really vaccines.

The Downside of Shame-Based Messaging

The headline for the third installment in the series says it all: “They’re idiots. Why don’t they trust us?”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Good Government Files to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.