The Risks of Ignorance

Michael Lewis provides a template for great government storytelling in The Fifth Risk

You’re probably familiar with author Michael Lewis. He wrote the bestsellers Moneyball, The Big Short and The Blind Side, all of which have been made into major motion pictures. When Brad Pitt, Christian Bale and Sandra Bullock star in your adaptations, you get noticed.

You may not be familiar with his book The Fifth Risk1, which published in 2018, even though it spent 14 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. If you follow national politics, you’re probably familiar with the news the book broke about President-elect Trump’s transition into the White House following his 2016 victory over Hilary Clinton. Or, more accurately, the lack of a transition. Lewis quotes multiple sources from Executive Branch agencies who were ready for extensive briefings with Trump appointees only to get no-showed.

I’m not going to get into the details about that — thought it’s really interesting reading and something to consider as you head to the polls later this year (it’s 2024, y’all!) to vote for President. Suffice it to say the Obama Administration spent months working to ensure an outstanding transition process, in part to pay it forward because of the terrific transition provided to it by the Bush Administration.

What’s much more interesting, particularly to those of us interested in the business of government, is what Lewis learns when he asks to get the briefings Team Trump missed out on at three Cabinet-level departments: Energy, Agriculture and Commerce.

What we get is an education about these agencies and the incredibly important work being done in them. The book also provides a lesson for why we have government agencies in the first place — to solve real problems that no one else is going to take on.

You might think learning about the departments of Energy, Agriculture and Commerce makes for deadly dull reading. Lewis uses his superpower of telling the big story through the compelling, highly personal stories of a few key people. Lewis draws you in as you come to know the backstories of these fascinating characters. He also shines a light on what these agencies actually do, and the magnitude and impact of their efforts.

To be brutally honest, I used to think of the federal government as a bloated bureaucracy that has little to no impact on my day-to-day life. When I look at what I pay Uncle Sam in personal income taxes every year, I wondered what the hell I’m paying for. Reading The Fifth Risk changed that.

There are lessons to be learned for all you government communicators among the GGF faithful, as well as anyone else who cares about effective governance. I think it was Hans Bleiker (star of the GGF post on public engagement) who taught me a couple of decades ago that you can govern only as well as you can persuade.

The Fifth Risk teaches us powerful lessons in persuasion, and the value of putting a face to our faceless bureaucracies.

The title comes from the first fascinating character Lewis introduces, John McWilliams of the Department of Energy (DOE). McWilliams didn’t set out to become a federal bureaucrat. He graduated from Stanford and Harvard Law School, but after a few years of lawyering decided he’d rather work in finance, so joined Goldman Sachs as an investment banker specializing in the energy sector. He got disillusioned with that after a time so quit at 35 to embark on his dream career — writing novels. He couldn’t get his first novel published but started on a second one anyway. The second one felt forced, so he jumped back into finance. (Of course, a publisher then called to say they were interested in his first book. Because, of course.) By that point McWilliams was too deep into starting up a private equity firm investing in energy companies to go back to writing. Smart move. After seven years, his firm was bought out for $500 million.

A nuclear physicist he met along the way asked him to join a task force at MIT to study the use of nuclear power. That physicist, Ernie Moniz, was named Secretary of Energy in 2013 and asked McWilliams to come work for him even though he had no government experience. Moniz was looking for talent. McWilliams said yes, noting he “always wanted to serve. It sounds corny. But that’s it.”

Lewis explains what the DOE does by taking us on McWilliams’ journey of discovery in his new job. Even thought he’d been investing in energy for decades, he really had no idea what DOE did. Like most federal agencies, its name is incredibly misleading. About half its budget goes to maintaining America’s nuclear arsenal and protecting citizens from nuclear threats. A quarter of the budget goes to cleaning up the “untold, world-historic mess” left behind by the manufacture of nuclear weapons. The last quarter goes to programs aimed at shaping Americans’ access to, and use of, energy.

McWilliams was the department’s first-ever chief risk officer. He became familiar with all aspects of the 115,000-employee department, which he describes as “the Office of Science” for America. The department’s mission is “to ensure America’s security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental and nuclear challenges through transformative science and technology solutions.” The DOE runs the 17 national labs — the Fermi National Accelerator Lab, Oak Ridge, Los Alamos, etc.

What I learned from the DOE website was that even though it has been in existence only since 1977, the Department traces its lineage to the Manhattan Project effort to develop the atomic bomb during World War II, and to the various energy-related programs that previously had been dispersed throughout various Federal agencies. I’m currently reading American Prometheus2, the biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer, known as the “father of the atomic bomb” that the movie Oppenheimer is based on. That book is totally engrossing as well, but the reason I bring it up is you may think McWilliams’ claim that the DOE is the Office of Science for America is hyperbole. It is not.

About That Title

The question Lewis sets out to answer in the book is this: What are the consequences if the people given control of our government have no idea how it works?

So, he sits down at McWilliams’ kitchen table, assuming the role of Trump appointee, ignores the thick briefing books and says, “Just give me the top five risks I need to worry about right away. Start at the top.”

Risk 1 is loose nukes and nuclear accidents. McWilliams tells the (now-declassified) story of a pair of 4-megaton hydrogen bombs — each more than 250 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima — that broke off a damaged B-52 over North Carolina in 1961. One disintegrated on impact but the other floated to the ground under its parachute and armed itself. Three of its four safety mechanisms tripped or were rendered ineffective by the plane’s breakup. Had the fourth switch flipped, “a vast section of eastern North Carolina would have been destroyed, and nuclear fallout might have descended on Washington, DC, and New York City.”

“The reason it’s worth thinking about this,” McWilliams says, “is the reason that bomb didn’t go off was because of all the safety devices on the bombs, designed by what is now DOE.”

Risk 2 is North Korean nuclear weapons. When Lewis was reporting for the book seven or so years ago, McWilliams told him there were signs the risk of some kind of attack by North Korea was increasing. Thankfully, nothing has transpired. Then again, two weeks ago the North Koreans conducted their first long-range missile test in months, and likely that of a solid-fuel rocket — which is harder to detect than liquid-fuel rockets. So, yeah, sure seems like a legit risk to worry about.

Risk 3 is ending the Iran nuclear deal. Moniz negotiated the deal that “removed from Iran the capacity to acquire a nuclear weapon,” Lewis writes.

That seems like an awfully bold declaration to me. Lewis explains:

There were only three paths to a nuclear weapon. The Iranians might produce enriched uranium — but that required using centrifuges. They might produce plutonium — but that required a reactor that the deal had dismantled and removed. Or they might simply go out and buy a weapon on the open market. The national labs played a big role in policing all three paths. “These labs are incredible national resources, and they are directly responsible for keeping us safe,” said McWilliams. “It’s because of them that we can say with absolutely certainty that Iran cannot surprise us with a nuclear weapon.” … (T)he serious risk in Iran wasn’t that the Iranians would secretly acquire a weapon. It was that the president of the United States would not understand his nuclear scientists’ reasoning about the unlikelihood of the Iranians’ obtaining a weapon, and that he would have the United States back away foolishly from the deal3. Released from the complicated set of restrictions on its nuclear-power program, Iran would then build its bomb.

Risk 4 is protecting the electrical grid from terrorism. It’s not just McWilliams worried about this one, but pretty much anyone Lewis spoke to at DOE. Lewis takes us to Oregon and describes his drive along the Columbia River, transitioning from lush forests to desert scrubland and the seeing multiple massive dams along the way. He informs us the river and its tributaries “generate more than 40 percent of the hydroelectric power” for the United States. He quotes a DOE staffer saying that basic necessities for humanity used to be “food and water.” Now, it’s “food and water and electricity.” Yup.

Remember when people were shooting at electrical transformers, about 10 years ago? I do, but never read this fact which Lewis shares: one night near San Jose, California, a “well-informed sniper” using a 30-caliber rifle had taken out 17 transformers. More alarming was that someone had also cut the cables that enabled communications to and from the substation where the transformers were shot. “They knew exactly which manhole covers were relevant — where the communications line were. These were feeder stations to Apple and Google.” There was enough backup power in the area to compensate, so the incident didn’t stay in the news. That’s a good thing. But in 2016 the DOE counted half a million cyber-intrusions into various parts of the U.S. electrical grid. That’s a bad thing.

As those of us who lived in Texas found out a few years ago during Winter Storm Uri, it took but one serious weather event to cripple the Lone Star State’s power grid for a week, an event that caused 246 deaths. So, yeah, huge risk.

Which leads us Risk 5: internal project management. Wait, what? How the hell does that rank with nuclear accidents, loose nukes, unhinged foreign leaders with control over nuclear bombs and the missiles needed to carry them to the homeland, and the possibility of losing the grid?

Meet the community of Hanford, in eastern Washington. That’s where Lewis was headed on his drive along the Columbia River. It’s the site the U.S. Army picked in 1943 to create enough plutonium for a nuclear bomb. Why Hanford? Lewis explains:

Hanford was chosen in part for its proximity to the Columbia River: the river supplied both cooling water, and electricity. Hanford was also chosen for its remoteness: the army was worried about both enemy attacks and an accidental nuclear explosion. And finally, Hanford was chosen for its poverty. It was convenient that what would become the world’s largest public-works project arose in a place from which people had to be paid so little to leave.

Hanford’s last nuclear reactor was shut down in 1987. The site had produced the material for 70,000 nuclear weapons. It was a phenomenal technical achievement but came at an enormous environmental cost that’s got to be cleaned up. There were 9,000 employed there to produce plutonium, and now there are 9,000 employed to deal with the mess. McWilliams conservatively estimates it will take 100 years and $100 billion to restore Hanford to what is legally required. The DOE ships 10 percent of its annual budget, or $3 billion, to Hanford to do just that. Two-thirds of all nuclear waste in the United States is there. To explain the severity of the problem, Lewis writes this: “Beneath Hanford, a massive underground glacier of radioactive sludge is moving slowly but relentlessly toward the Columbia River.” How is that possible? Because in the rush to ramp up production of nuclear bombs to counter the Soviet threat in the 1940s and early 1950s, “they simply dumped 120 million gallons of high-level waste, and another 440 billion gallons of contaminated liquid, into the ground,” Lewis writes.

The risk here is that politicians don’t take the time or interest to truly understand the problem and cut the DOE budget — making a short-term political decision with massive long-term repercussions. As you’ve learned now, the DOE has very little to do with energy and lots to do with keeping our people safe from unimaginable amounts of radioactive material that could kill or maim them.

Another way to think about McWilliams’ fifth risk, Lewis writes, is to consider what happens when our government “falls into the habit of responding to long-term risks with short-term solutions.”

“Program management” is the existential threat that you never really even imagine as a risk. Some of the things any incoming president should worry about are fast-moving: pandemics, hurricanes, terrorist attacks. But most are not. Most are like bombs with very long fuses that, in the distant future, when the fuse reaches the bomb, might or might not explode. It is delaying repairs to a tunnel filled with lethal waste until, one day, it collapses4. It is the aging workforce of the DOE — which is no longer attracting young people as it once did — that one day loses track of a nuclear bomb. It is the ceding of technical and scientific leadership to China. It is the innovation that never occurs, and the knowledge that is never created, because you have ceased to lay the groundwork of it. It is what you never learned that might have saved you.

In the ensuing chapters, Lewis goes through the same exercise with the departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Commerce. They, too, are inaptly named. The USDA has little to do with agriculture. It runs 193 million acres of national forests and grasslands; it inspects almost all the animals Americans eat; it’s got a massive science program, etc. It basically supports rural America. Ironically enough, the Commerce Department is forbidden by law from engaging in business. It runs the U.S. Census and collects and makes sense of all the country’s economic statistics. It also houses and spends more than half of its $9 billion budget on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Every day, “the NOAA collects twice as much data as contained in the entire book collection of the Library of Congress.”

My Takeaways

The story of government is the story of people. Like Lewis, we need to tell the stories of the people in our agencies while we’re also telling the stories of the work they are doing.

For example, he begins the chapter on USDA by giving the background of Ali Zaidi, whose parents immigrated from Pakistan to the United States in 1993. Ali went from living in Karachi, a city of more than 8 million Muslims, to a town of 7,000 mostly Christians in northwest Pennsylvania. They went from solidly middle class in Pakistan to poor in the United States. Ali is smart and hardworking, so makes his way to Harvard and lands a job in the Office of Management and Budget. His job was to take budget numbers produced by senior staff and write a narrative that regular folks could understand.

One day he’s handed the USDA budget and thinks “they give money to farmers to grow stuff.” Wrong. As he dives into the numbers, he has a realization. “The USDA had subsidized the apartment my family lived in. The hospital we used. The fire department. The town’s water. The electricity. It had paid for the food I had eaten.”

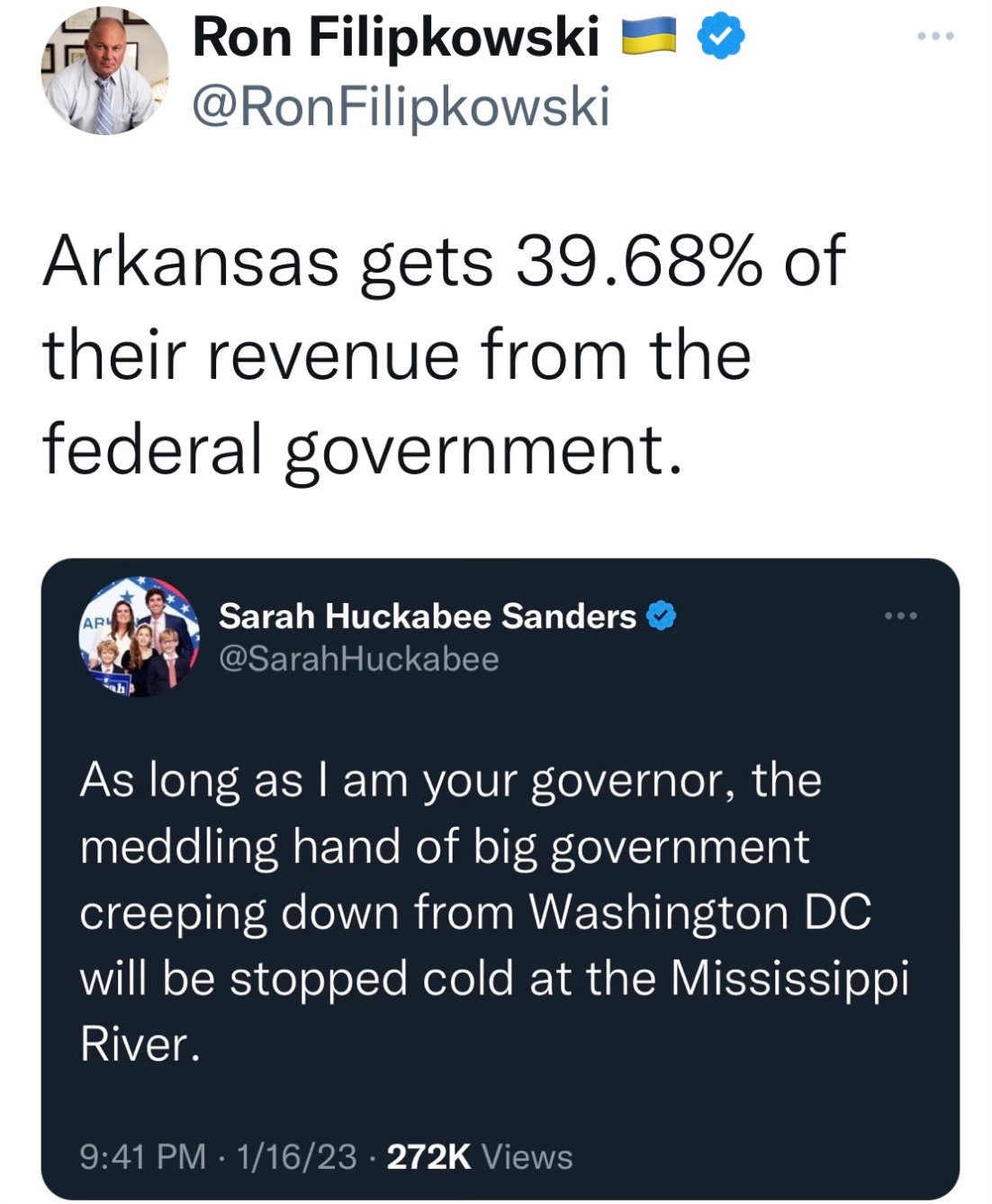

A lot of the money USDA funnels into rural America runs through local banks. Often, the recipients have no idea where the money is coming from. Lewis tells the story of a small-town businessman in Minnesota who’s being recognized by the local bank at a ceremony. He’s crowing about making it “on his own.” He meets a rep from USDA and wonders aloud what she’s doing there. She informs him the federal government supplied the money the bank was announcing. “He was white as a sheet.”

“In the red southern states,” a USDA staffer tells Lewis, “the mayor sometimes would say, ‘Can you not mention that the government gave this?’ … It’s just a misunderstanding of the system. We don’t teach people what the government actually does.”

You would think a former White House press secretary would know what the government actually does. Apparently not.

Teach people what the government does. Yes. I heard an analogy a few years back that has always stuck with me. Southern California local gov legend Rick Cole was giving the opening keynote at the 3CMA annual conference. He said many citizens likened government to a vending machine. They put their money in, services come out, but they have no idea what’s going on inside the box. When they don’t get what they want, they bang on the side of the machine in frustration, i.e., write snarky comments on the city Facebook page or go on a three-minute rant at a city council meeting.

Is it hard to get people to pay attention to what’s happening in local government? You bet it is. And it’s not about to get any easier. We are about to embark on an election season like none we’ve seen before. The likely GOP nominee will be in court fighting 90-plus felony counts in four states. On the other side, 69 percent of members of his own party think the incumbent Democrat is too old to serve effectively.

Yet press on we must. Despite there being so much clutter to break through, we’ve got to find ways to get citizens interested in the dark box that contains government service and create compelling ways to tell our story. We’ve got talk about the problems we’re solving in local government that no one else will take on. I think The Fifth Risk shows us it can be done.

Onward and Upward.

Paid link. As an Amazon associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Ibid

Which is exactly what happened.

That actually happened in Hanford in 2017. The dirt used to fill in the collapse is now considered low-level radioactive waste and needs to be disposed of. Sigh.

The Federal Register is the best place to find proposed rulings. It is not visually appealing as it includes texts of proposed laws. Maybe the Federal government needs a PIO providing meaningful and concise info to the general public on a daily basis?

https://uvu.libguides.com/government-information/main-sources#:~:text=The%20Federal%20Depository%20Library%20Program%20(FDLP)%20Basic%20Collection%20consists%20of,of%20the%20US%20Federal%20Government.

1. Like you, I felt that the Feds were just there, until the last 8 years. I also thought that as long as the Texas legislature met every other year, what harm could they cause. Ha!

2. Below is a link with an update on radioactive waste remediation going on in Hanford. Since the Columbia River is about 10 miles from my home, your article definitely had me searching for more info.

Thx!

https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.cleanup&id=1001114#:~:text=Cleanup%20activities%20completed%20to%20date,fuel%20and%20associated%20waste%3B%20and