Wheels of Change: Erik Erazo's Vision for At-Risk Youth

How the Olathe Leadership Lowrider Bike Club is Building Community and Transforming Lives

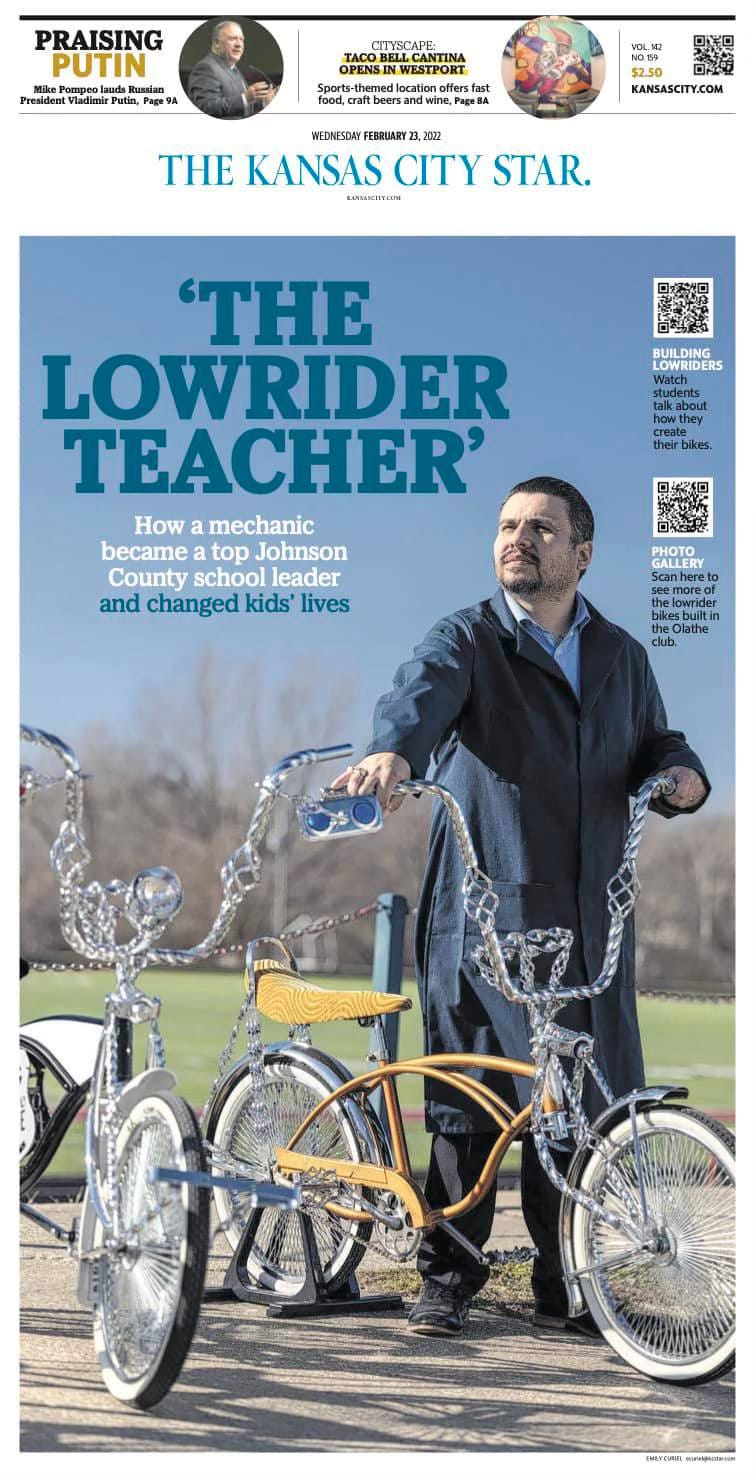

Welcome to the fourth installment of Good Government Files’ Servant Leaders Series. Each story in this series, drawn from presentations at the annual Servant Leadership Conference hosted by SGR1, showcases remarkable individuals making a difference in their communities. Today, we highlight Erik Erazo, a visionary known as the ‘Lowrider Teacher’ by the Kansas City Star, and his transformative initiative, the Olathe Leadership Lowrider Bike Club.

The start of Erik Erazo’s journey in life certainly didn’t foreshadow the kind of success he would see as a school administrator. Then again, he’s not your average public education bureaucrat. Then again, again, his story is all about what can happen when you catch a break or two in life and resolve to pay it forward.

Early Struggles

He grew up in a “kind of a rough” neighborhood in San Francisco. He was a father at 16 and dropped out of school to take care of his daughter. By 18, he had a second child by a different woman (who is now his wife). He picked up a mail-order high school diploma from a company he read about in a low-rider magazine. When he tried to enroll in an automotive technology school, they ignored the diploma and required him to take a test to demonstrate basic proficiency in math and language. He failed, twice. A third strike meant he would have to wait six months to take it again.

“I knew that given my situation and what I was living through, that there’s no way that in six months I was going to come back and take that test,” he said.

He recalled seeing a basic literacy course advertised at the local library (God bless our wonderful libraries!) and signed up. At least, he tried to sign up. They said, nope, there’s services for kids like you at the public school. That wasn’t an option because, he said, he had a restraining order from the school district. A retired teacher decided to take him on.

“She was like, you know what, let me work with this kid. I think I can help him out,” Erik says. “Thank God. So, this lady was working with me, and she taught me the basics and where a period goes and how to capitalize — and I am not making that up. Like, I didn’t even know my ABCs.”

He takes the basic test for the auto school a third time and passes. Two years later, he’s got his associate’s degree from the Sequoia Institute of Automotive Technology. His first day on the job at a dealership, he runs into an old friend from the neighborhood.

“And the dude’s like, ‘What’s up, homie!’ I’m like, ‘Oh no, man,’” Erik recalled. “Needless to say, things didn’t go well that very first day. And the service manager came out and he’s like, man, this ain’t gonna work out, kid … I was, like, devastated because I was like, man, I just did two years of (school) so that I can get out of this (old life). Like, I’ll never be able to survive.”

So, he loads his tools into the trunk of his car and starts driving — and thinking.

“I got these two kids. What am I going to do? And so, I just prayed as hard as I could, and I said, ‘Lord, show me a sign. What do I need to do next?’”

Right in his eyeline was a recruiting billboard for the U.S. Army.

“I was like, dang, Lord, you showed me a real sign. That’s what’s up. That’s awesome.’ So, I still have my tools in the back of my car, and I went to the recruiting office over at the mall, and I went in there and I talked to the sergeant. I said, ‘Sarge, if I join the army can you get me out of here?’ He’s like, ‘Yeah, we can definitely make that happen.’”

Seven months later, Erik is stationed in Germany. While there, his wife gives birth to twins.

“So, yes, if you’re counting, I’m in my early 20s with four kids.”

Turning Points

Rather than re-upping and heading to Iraq, he discharges from the Army and returns to California. While he had changed, things were pretty much the same back at home.

“It felt like time had stood still. I don’t know if you ever had that feeling, if you’ve ever gone back somewhere. And it’s like, dang. Like, I feel like I did a whole bunch of stuff, but nothing actually happened back here. And it was super frustrating. I can tell you one conversation that I had in particular that just blew my mind. Like, I felt like I had grown up. I had a car payment; I had done all this grown-up stuff. I go back to where I’m from, and I’m talking to one of my old homeboys that I grew up with, and he’s like, ‘Homie, you know what? I’m gonna get a job.’ I said, ‘That’s good, bro.’ He’s like, ‘I’m gonna save.’ I was like, ‘Yeah, that’s what’s up!’ He’s like, ‘And then I’m gonna buy a pound.’ And I was like, I don’t need to be here.”

He left for Kansas, where some of his family members had relocated. He applied for a job with a security company. Given his military background and the fact he’s bilingual, he’s hired. He’s assigned to provide security at … wait for it … Olathe North High School. He’s not crazy about the assignment, but needs the work, so it’s back to school.

He sees the Hispanic kids in Kansas acting like the gang bangers he grew up with in Cali. Many were members of migrant families who recently moved to the area to do construction work. Unlike in his old neighborhood, the Kansas suburbs were safe. Look out the window and you don’t see drive-by shootings, you see “a lady jogging with her dog.” But the appeal to gang membership is the same; kids “trying to fit in somewhere,” he said.

“I was like, man, that is not good. I don’t want kids to have to do that here. It’s pointless. That stuff is toxic. So, I go up to counselors, and I’m like, ‘Hey, you need to talk to this kid about this.’ And they’re like, ‘Why don’t you talk to him?’ I’m like, ‘Nah, man. That ain’t my thing.’”

The Birth of the Bike Club

But it becomes his thing. Long story short, Erik earns his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in education. He sees data showing a strong correlation between high school dropouts and gang involvement.

“Wherever you see a lot of kids dropping out, you see a lot of gangs. And why is that? What we found was the main reason is (something) gangs figured out, that we’re just discovering in education, is relationship building.”

What he realized is that trying to intervene in kids’ lives at the high school level is intervening too late. Gangs start introducing themselves to kids in elementary school. By middle school, they begin to give them some responsibility. By the time they’re in high school, their entire lives revolve around gang membership.

His first project was a leadership program for elementary school students. It continued into middle school and giving the students more responsibility, “college trips, fundraisers, all kinds of fun stuff.”

“And then, by the time they’re in high school, they’re in too deep to quit.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Good Government Files to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.